The International Colonization Memorial & Museum (ICMM) as a public institution that will be open to all, where anyone is welcome to participate, collaborate, and learn more about colonization, and how their stories, their histories, and their cultures were shaped and informed by racial terrorism, need things as powerful and as important as a people, and as a nation that is steeped in its history.

To trace colonization from the people and the nations of the Americas that have explored and preserved this important history for centuries, RHI will liaise/work with the Ambassadors and Diplomatic Representations of countries of the region in the United States, including their educational institutions – for data archiving, so that ICMM will tell their story through the lens of all the sovereign states, overseas departments, and dependencies of the Americas.

An honest confrontation of colonization and the willingness to acknowledge and admit our history of racial injustice, reconcile its painful legacy, especially our ancestors – Native American Indians, as well as Black folks (not exclusively), who were killed in the worst of circumstances, is a major first step towards racial healing.

The write-up below explains why an in-depth history of colonization in the Americas is pivotal for ICMM

Colonization in the Americas

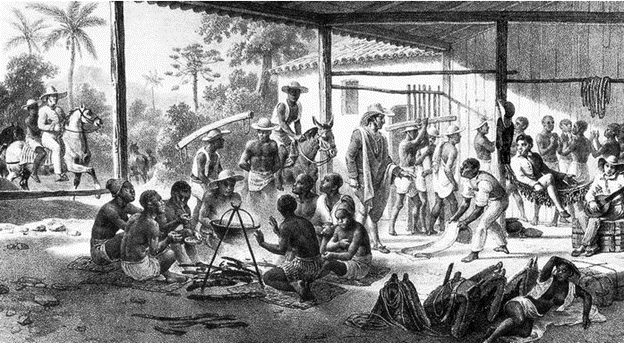

15th century Portuguese slave hold in Brazil (public domain image)

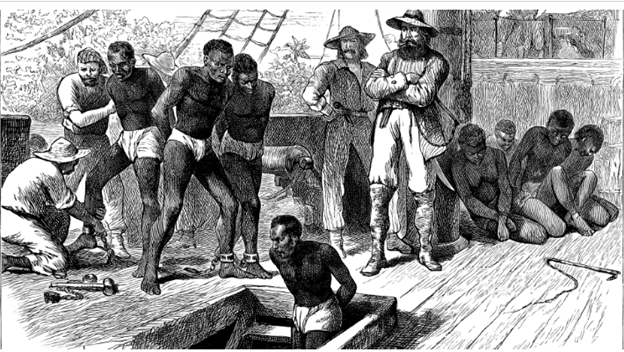

Captives being brought on board a slave ship on the West Coast of Africa (Slave Coast), c1880. (Ann Ronan Photo) public domain image

Colonization in the Americas began in the 15th century when Spain and Portugal started sending ships on expeditions to find new trade routes to Asia. The outcome of this search was the discovery by Christopher Columbus in 1492 of land, a “New World” in the Western Hemisphere. This New World - mile upon mile of plains, fertile farmlands, valleys, pastures, and mountains contained all the natural wealth, including great deposits of gold and other minerals which European powers sought so eagerly.

Europeans looked on the original Indigenous occupants of the Americas as primitives or savages who would benefit from the introduction of European civilization and religion. They also viewed the Americas as an enormous wilderness area with great economic potential and were determine to either forcefully, or dubiously gain control of the wealth. To achieve their objective, they claimed and insisted that the Indigenous peoples of the Americas were not owners of the land, although millions of their people had already settled in the lands thousands of years earlier.

The original occupants of the Americas were the ancestors of the peoples now known collectively as the Indigenous peoples of North America (also called in different places First Nations, Native Americans, or American Indians). At the time of European contact, the numerous Indigenous peoples spoke more than 800 different languages and lived throughout the Western Hemisphere. They ranged from nomadic hunter-gatherer cultures to agricultural societies with highly developed empires and sizable cities.

Numerous European expeditions sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to explore this vast new land, and other explorers began arriving at mainland North America, which also includes Central America, and South America. Soon, they began to explore the land, eventually, claiming, colonizing, and building colonies.

The first European countries to begin colonizing the Americas were Spain and Portugal. Spain claimed and settled Mexico, most of Central and South America, several islands in the Caribbean, and what are now Florida, California, and the Southwest region of the United States. Portugal gained control of Brazil. Today, the region encompassing Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean islands is known as Latin America. Because of its colonial history, most of its people speak Spanish or Portuguese.

In North America, France colonized Canada and the valleys of the St. Lawrence, Ohio, Mississippi, and Alabama rivers. France also took control of French Guiana, on the northeast coast of South America, and a few Caribbean islands. The Dutch settled in the Hudson River valley of North America and in some island territories in the Caribbean. They also colonized Dutch Guiana (now Suriname) and what later became British Guiana (now Guyana), in northern South America. Sweden laid claim to the Delaware River valley in North America. Russia founded colonies in Alaska. England eventually ruled 13 colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America, settled British Honduras (now Belize) in Central America, and took possession of British Guiana and several Caribbean islands.

And so, the period of exploration and discovery soon became an international race to plant colonies around the world. The European countries of England, France, Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands (Holland) vied with one another for nearly four centuries to gain economic advantages in overseas territories.

European colonization of the Americas brought ruinous changes to Indigenous peoples and their ways of life. The Europeans introduced diseases to the Americas that decimated Indigenous populations. Europeans also enslaved large numbers of Indigenous people, seized Indigenous land, and destroyed native cultures and religions.

Many of these colonies were financed by European-based trading companies. These companies sought riches in the crops, furs, and minerals of the New World. Trading groups were granted large areas of land by European governments, which expected in return some of the riches of the Americas and secure settlements to uphold their territorial claims. The managers of the colonies worked their lands with servants, enslaved Indigenous or Black African people, or tenant farmers.

Colonizing countries fought among themselves and against local Indigenous people for control of the land and its trading possibilities. Wars in Europe had their counterparts in nationalistic rivalries among American colonists. It was not until the 19th century that most colonial disputes were ended either by treaty or by national independence movements. The Americas now consist largely of independent countries.

Spanish Colonization of the Americas

Spain was the first of the European countries to colonize the New World. In land area, Spain was also the largest of the colonial empires in the New World. It comprised several islands in the West Indies, all of Mexico, most of Central America; most of South America except for Brazil, and what is now Florida, California, and the U.S. Southwest.

The Spanish had the advantage of nearly a full century to stake its claims. People from France, England, Holland, and Sweden did not settle in the Americas until after 1600.

By 1512 the Spanish had occupied the larger Caribbean islands. The first Spanish towns were established on the island of Hispaniola (now divided politically into Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Chief among these towns was Santo Domingo, which was established in 1496 and became the first capital of Spain’s New World possessions. Other Spanish settlements arose in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Jamaica. From island harbors Spanish expeditions sailed to explore the coasts and penetrate the continents. They found gold, silver, and precious stones and enslaved the Indigenous peoples. Ambitious men became governors of conquered lands. Christian missionaries brought a new religion to Indigenous peoples. The Spanish dream of finding great riches in the Americas was first realized when Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztec Empire in Mexico in 1519–21. A few years later Francisco Pizarro with a small force vanquished the Inca Empire and seized the treasure of Peru in South America. Gold and silver from these lands poured into the Spanish king’s treasury, rousing the envy of other rulers.

The rich finds of gold and silver in Mexico and Peru prompted Spain to organize expeditions to the surrounding areas. Spanish conquerors (called in Spanish conquistadores) began taking control of Central America and many parts of South America. Other conquistadores ventured north into the southern parts of what is now the United States. The great majority of the conquistadores ruthlessly pursued gold, power, and status.

At the same time, Spanish Roman Catholic priests, including Jesuits, Franciscans, and others, worked to convert Indigenous peoples to Christianity. They often led the movement into frontier areas, bringing along European culture and establishing educational institutions and religious missions.

A controversial aspect of Spanish colonialism was the encomienda system, an arrangement under which the government “commended” (or entrusted) the care of the Indigenous people in a particular area to a conquistador, official, or other Spaniard. It was in fact a system for enslaving the Indigenous people and forcing them to work in the mines, farms, and ranches. Theoretically at least, the Spaniards cared for the Indigenous people’s physical and spiritual needs in return for the right to their labor. In practice, Indigenous people were often abused and exploited. While some Spanish friars and priests condemned such slavery as early as 1515, landowners resisted the movement to abolish the encomienda.

Indigenous people living in areas controlled by the Spanish died in great numbers from the violence of conquest, exploitation, and especially diseases, such as smallpox, from which they had no immunity. The Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean virtually disappeared. The estimated 50 million Indigenous people living in the mainland areas at the time of their colonization had dwindled by the 17th century to only 4 million. As the numbers of Indigenous people available for forced labor dropped, the Spaniards shipped increasing numbers of enslaved Africans to their American colonies, especially in the Caribbean.

Spain’s colonies north of the Rio Grande were lost to the United States in the 19th century. Florida was given up in 1819, and war with Mexico brought the Southwest territories into the hands of the United States government in 1848.

Spain’s holdings in Mexico, Central America, and South America were lost between 1810 and 1825 through a series of revolutionary movements. Only the islands of Puerto Rico and Cuba remained as colonies, and these were lost in the Spanish-American War in 1898.

The end of colonialism in Spanish America was prompted by a variety of factors. The American and French revolutions in the late 18th century inspired other peoples to strive for self-determination. The immediate impetus to decolonization came in the Napoleonic Wars in Europe between 1803 and 1814. French occupation of Spain and Portugal in 1807 served to isolate the American colonies from the mother countries. This isolation, coupled with long-smoldering discontent in Latin America, led to the formation of nationalist and revolutionary movements. Spain and Portugal, on the other hand, were too weakened by war at home to respond forcefully to troubles in the Americas. They could not count on help from England in retaining their colonies. English merchants were eager to trade with the newly independent countries of Latin America, which would not have colonial trade restrictions.

In 1823, during the presidency of James Monroe, the United States proclaimed the Monroe Doctrine declaring against any further colonization or interference by Europe in the affairs of the Americas. With the help of the British navy, this doctrine forestalled any new colonial enterprises for several decades.

Portuguese Colonization of the Americas

Although the Portuguese were among the earliest and most prominent world explorers, their efforts in the New World centered entirely on Brazil. After Spain made its first discoveries in the Western Hemisphere, a conflict arose between Spain and Portugal concerning colonization rights to the New World. In 1494 a north-south Line of Demarcation was established at about 1,185 miles (1,900 kilometers) west of the Cape Verde Islands. All territory east of the line fell to Portugal, while all territory west of it went to Spain. This agreement was called the Treaty of Tordesillas. The signers of the pact were not yet aware of the extent of the Western Hemisphere. By chance it happened that the region of coastal Brazil in South America became the possession of Portugal.

Brazil was “discovered” by the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvarez Cabral in 1500, though the new land was of little interest to Portugal until 1530. Portuguese farmers grew sugarcane for export to Europe. Sugar was first cultivated in Brazil in 1620, initially using Indigenous slave labor. The Portuguese increasingly began to rely on enslaved Africans, importing some four million Africans to Brazil from the 1500s to the 1800s.

In 1580 Philip II of Spain seized the throne of Portugal. Brazil came under the control of Spain until 1640, when Portugal’s independence was restored. Brazil remained a Portuguese colony until 1822, when a bloodless revolution set up an independent monarchy.

The Portuguese introduced slaves from Africa into Europe in the 15th century. After Europeans discovered the Americas and began settlements there, the Portuguese and the Spanish introduced slave labor into their American colonies.

English Colonization of the Americas

Although the English colonized areas throughout the New World, their most significant establishment proved to be the 13 colonies along North America’s Atlantic coastline. These communities, weak and struggling at first, grew and developed to become the 13 original states of the United States of America.

The first permanent English settlement was Jamestown, which was established in 1607, present day Virginia. The second English settlement was Plymouth, founded in 1620, now Massachusetts. This colony was later absorbed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The English also settled New Hampshire (1623), Maryland (1634), Connecticut (1635), Rhode Island (1636), Carolina (1653), Pennsylvania (1681), and Georgia (1733). North Carolina and South Carolina became separate colonies in 1730. The region comprising the four most northerly English colonies—Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire—became known as New England. Today, New England also includes Maine and Vermont.

New York (1624) was originally colonized by the Dutch as New Netherland. This colony also included the first permanent settlement in New Jersey (1660). The Swedes founded the first permanent settlement in Delaware (1638), as part of their colony of New Sweden. In the 1650s the Dutch captured New Sweden and made it part of New Netherland. The enlarged Dutch colony in turn fell to the English in the 1660s. All the 13 colonies thus became English in speech and customs within a couple of generations.

English reign over the colonies barely served to conceal the great ethnic diversity of the settlers. The 17th century saw the arrival of Germans, Bohemians, Irish, Poles, Scots, Jews, Dutch, French, Finns, Italians, Swedes, Danes, south Slavs, and other nationalities. Slave ships brought blacks from the west coast of Africa. Of the non-British colonists, the Germans who settled heavily in Pennsylvania and Georgia were probably the most numerous.

Throughout the whole colonial era there was a persistent labor shortage. The need for an adequate work force led to the development of the systems of indentured, redemptioner, and slave labor.

Indentured servants were immigrants too poor to come to America on their own. They sold themselves under contract into specific periods of servitude, usually from three to seven years. After the time was up, a servant was freed from his obligation, given whatever money was due to him, and invested with the rights of citizenship. Redemptioners were also immigrants too poor to get to the colonies on their own, but they arrived without labor contracts. If no relative or friend paid for their passage, the ship’s captain sold them to the highest bidders for unspecified periods of service. If they managed to earn enough money, in a few years they could “redeem” themselves and be free. Otherwise, they were likely to become and remain slaves. The indenture and redemptioner systems were legally sanctioned arrangements that slowly disappeared because of disuse and public disapproval. The slave system was to persist in the Americas until the 19th century. The development of the slave trade from Africa and the exploration of the New World were almost simultaneous events.

Before long the great ship companies of Europe were competing for this very profitable trade. At first most of the slaves went to the Caribbean islands. After the economies of the English colonies of North America began to prosper, slaves were introduced there. The first slaves were brought to Virginia in 1619. In the 18th century the English became the chief suppliers of African slaves to the New World.

The earliest English colonies - Virginia, Plymouth, and Massachusetts Bay - were founded by “joint-stock” companies. These private companies raised the money for colonization by selling shares to investors, who became partners in the venture. The companies operated under charters issued by the king of England. The colonies of Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire were offshoots of Massachusetts Bay.

Maryland and Pennsylvania were founded as proprietary colonies: the king of England gave grants of land to individual entrepreneurs to start a colony. The entrepreneurs became the proprietors, or owners, of the colony. Maryland was founded by Cecilia Calvert (Lord Baltimore), and Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn. Settlers of these colonies were tenants of the proprietor, rather than landowners. Eventually all the other colonies except Rhode Island and Connecticut came under the jurisdiction of the English crown.

The Carolinas were founded as a proprietary colony but later came under the king’s control. Georgia was started as a philanthropic enterprise, a haven for debtors and other underprivileged English people. It too became part of the king’s domain.

Whether royal or proprietary, all the 13 colonies eventually had their own representative assemblies and local institutions of government. Self-rule flourished in the Atlantic colonies because they were remote from England and communication was slow. England also did not value them as highly for their economic potential as it did its colonies in the Caribbean and India. In addition, the English Civil War and other troubles in Europe kept the mother country too occupied to bother with the distant colonies for long periods of time. Theoretically, the only bond of union common to the colonies was their loyalty to the king. It was the king who appointed colonial governors, and these officials were expected to carry out royal policy.

As the decades passed, however, the colonies found themselves drawn together by stronger ties than the monarchy. Their representative assemblies were quite similar in character. All the colonies had similar agricultural economies, and hence similar problems. Improved roads and shipping made communication easier. To the west, all the colonies faced the common enemy of New France and its Indigenous allies.

This variety of common interests eventually provided the basis of common action when English policies became oppressive. Until the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, England had not overly interfered in colonial life. After 1763 it began enforcing restrictions on manufacturing and trade. Parliament levied direct taxes on the colonies to help it pay its military budget. These new policies led to revolution in 1775 and to independence in 1776.

The Caribbean and South America

Besides ruling the 13 colonies of North America, England settled other parts of the New World. In the Caribbean, the English colonized the Leeward Islands of Antigua, St. Kitts, Nevis, and Barbados between 1609 and 1632 and seized Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655. In Central America, British buccaneers and loggers began settling in Belize in the 1630s. Scattered settlements on the north coast of South America were united into the colony of British Guiana (now Guyana) in 1831.

Of all the English settlements in the Caribbean basin, Barbados was the most successful commercially. By 1651 it was a leading producer of sugar. This commodity, much in demand by Europeans, was introduced into the island about 1637. By 1676 the sugar trade had promoted Barbados to a first-rank colony in the eyes of England. Its population was larger than that of New England, and it was far more prosperous.

Barbados was typical of the colonized Caribbean because it was not settled entirely by Europeans; rather it was captured by them and settled mainly with slaves and servants to work the fields. Millions of slaves were forced into labor on the islands during the three centuries from 1500 to 1800. The first English slave-trading voyage was made by John Hawkins in 1562. After the British slave trade ended in 1807, plantation owners imported indentured servants from China, India, and Java.

French Colonization of the Americas

The largest French colony in the New World was New France. This region comprised most of what are now eastern Canada and the portion of the United States from the Appalachians in the east to the Missouri River in the west and from the Great Lakes in the north to the Gulf of Mexico in the south. To the north of New France was the large territory controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company, an English trading association.

Starting about 1540, French fishers annually fished off the Newfoundland coast and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The first colonization efforts were led by Samuel de Champlain, the “Father of New France.” He helped founded the colony that became Port-Royal (now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia). This fur-trading post and fishing village was the first organized settlement in Acadia (the French possessions on the Atlantic seaboard) as well as the first permanent European colony in North America north of Florida. Champlain founded Quebec in 1608 and explored as far west as Lake Huron by 1615.

Even though the French tried and failed to settle Brazil, the Carolinas, and Florida, they had greater success in the Caribbean. On the northeast coast of South America, the colony of French Guiana was founded about 1637, and by 1664 France controlled 14 islands in the Caribbean. The principal possessions were St-Domingue (now Haiti), Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Dominica. The economies were based largely on sugar. The labor system was African slavery. The island societies had a rigid class structure headed by white officials and planters (gros blancs) who governed the merchants, buccaneers, small farmers, white laborers (engagés), and slaves.

The main interest for French colonizers was commercial exploitation. The fur trade, far more lucrative than farming or fishing, became the basis of the economy. This led the French to explore widely in the region, to forge strong alliances with the local Indigenous people, and to set up forts and trading posts. But the population of New France never grew to the same extent as that of the English colonies. By 1754, on the eve of the French and Indian War, the population of New France was only about 55,000.

During the 17th century a vast number of Frenchmen—traders, missionaries, and soldiers—traversed the wilderness from eastern Canada to New Orleans. They ventured throughout the whole Great Lakes region and the Mississippi Valley, claiming the territory for the king of France. Within this vast midsection of North America, many permanent settlements were founded, including Detroit, St. Louis, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans.

During the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries, France and England were frequently at war. The wars they fought in Europe generally had counterparts in the colonies—King William’s War (1689–97), Queen Anne’s War (1702–13), King George’s War (1744–48), and the French and Indian War (1754–63), a phase of Europe’s Seven Years’ War.

These wars were generally detrimental to France’s colonial holdings. After Queen Anne’s War, the British acquired French Acadia, renaming it Nova Scotia. The French and Indian War was the costliest for France. By 1760 the British had conquered all of Canada and the French settlements on the Great Lakes. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the conflict, ceded New France east of the Mississippi River, except for New Orleans, to England. New France ceased to exist in 1803 when the United States purchased the territories west of the Mississippi from France, in what is known as the Louisiana Purchase.

Netherlands Colonization of the Americas

The Netherlands began exploring the New World in the early 17th century. For years the Dutch struggled to win their independence from Spain. When Spain annexed Portugal in 1580, the Spaniards gained control of the Asian trade. The Dutch realized that Spain might be weakened by striking at its trade. They formed the Dutch East India Company and dispatched Henry Hudson, an English sea captain, to find a shortcut to Asia. Hudson entered the Hudson River in 1609 and ascended it to the site of what is now Albany, New York.

The settlement of the Dutch in the New World was led by commercial traders under the sponsorship of the Dutch West India Company, a joint-stock company founded in 1621. Three years later the Dutch colony of New Netherland was founded in what is now New York State. About 1626 the city of New Amsterdam was founded on Manhattan Island (now the heart of New York City).

Peter Minuit of the Dutch West India Company “purchased” the island from local Indigenous people with trinkets valued at 60 guilders (often said to be worth $24). However, the Indigenous people did not recognize any private ownership of land and so probably believed that they were agreeing only to share the island. The Dutch built 30 houses on Manhattan that same year.

The first colonists from the Netherlands included free citizens, who could own their own homesteads and receive two years of free provisions. Other colonists were indentured servants, who had to work under contract for a term of service on Dutch West India Company farms. In 1629 the Dutch established the patroon system. Patroons were free citizens given large grants of land by the Dutch government. They held such rights as the privilege of holding court hearings in their areas. There were five large patroon land grants settled along the Hudson River from New Amsterdam to Fort Orange (now Albany, New York).

As the colony expanded, violent conflicts broke out between Dutch colonists and local Indigenous people.

Even more devastating to the Dutch were their conflicts with the English. In 1653 the Dutch built a wall across lower Manhattan Island to defend their city against any English or Indigenous attacks. This is the wall for which Wall Street—the financial center of New York City—is named. In 1664 English military forces captured New Amsterdam, renaming it New York in honor of the Duke of York. Although temporarily retaken by the Dutch, New York became permanently English under the terms of the Treaty of Westminster in 1674.

The Dutch tried and failed to colonize Brazil between 1624 and 1654. They did succeed in planting one other colony in South America and several in the Caribbean. They settled Dutch Guiana (now Suriname), in northern South America, and six Caribbean islands: Curaçao (taken from Spain in 1634), Aruba, Bonaire, Saint Eustatius, Saint Martin, and Saba. Presently Aruba, Curaçao, and Saint Martin are autonomous countries within the Netherlands, while Bonaire, Saba, and Saint Eustatius are special municipalities within that country.

Swedish Colonization of the Americas

Sweden entered the race for the colonization of the New World in the 1630s with the formation of the New Sweden Company. Peter Minuit of the Dutch West India Company switched his loyalties from the Dutch to the Swedes and helped found Fort Christina (now Wilmington, Delaware) on the Delaware River in 1638. In 1643 the Swedes expanded to a settlement of log cabins at Tinicum Island, also on the Delaware River. It was the first European settlement in what is now Pennsylvania. The Swedes also established Fort New Korsholm near the mouth of the Schuylkill River in 1647. They captured Fort Casimir (now New Castle, Delaware) from the Dutch in 1651. Fort Casimir was especially critical because it protected the route to the rest of the Swedish colonies. In 1655 the governor of New Netherland, Peter Stuyvesant, seized Fort Christina and recaptured Fort Casimir, making New Sweden a part of New Netherland.

The expansion of Russia into North America began during the reign of Peter the Great, the Tsar who ruled from 1689 to 1725. He was determined to compete with other European countries in getting a foothold in the New World. The expansion of the Siberian fur trade motivated the explorations that eventually resulted in the European discovery of Alaska.

Shortly before his death, Peter commissioned Capt. Vitus Bering, a Dane serving in the Russian navy, to investigate a possible land connection between Siberia and North America. Bering’s first voyage, in 1728, failed in locating one. On his voyage of 1741 he did arrive at the southern coast of Alaska. His ship was wrecked, however, and he died there. The expedition’s survivors returned to Russia with sea-otter pelts. For the next several decades the Russians exploited the fur trade of the region.

Russians established communities and fur-trading posts at Captain’s Harbor on Unalaska Island in 1773, Kodiak in 1792, and New Archangel (now Sitka) in 1799. As the Russians moved into Alaska, other European trading groups and colonial powers began to converge on the area. To fend off competition, a trading monopoly, a Russian-American Company, was formed in 1799. New Archangel became the center of all the company’s commercial activity. Besides the Russian trading post, the settlement had a shipbuilding industry, a foundry, a sawmill, and a machine shop.

Because the Russians in Alaska were unable to achieve self-sufficiency in agriculture, they founded a new colony, Fort Ross, in northern California in 1811–12. They hoped that the farms in this area would be able to supply enough food for the residents of Alaska. This venture never became profitable, and Fort Ross was abandoned in 1841.

The Russian government repeatedly tried to maintain a fur monopoly in Alaska and to control the waters surrounding the colony. Despite its efforts, Europeans and Americans began to move into the region during the first half of the 19th century. By 1850 hundreds of non-Russian whaling vessels were operating near Alaska. The great distance of Alaska from the Russian capital at St. Petersburg made it virtually impossible for the Tsar to enforce any regulations or prohibitions.

With the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853, Russian forces had to be concentrated in Europe. This meant that Alaska, so far away, could not be securely held and defended. In 1857 the Russian minister to the United States suggested that Alaska might be for sale. The American Civil War prevented any transaction from taking place immediately. Finally, in 1867, a treaty was negotiated by U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward by which the United States purchased Alaska for 7.2 million dollars.

End of Colonization in the Americas

For the most part, the countries of the Western Hemisphere became independent from Europe in the 50-year period from 1775 to 1825. The United States won its independence in 1776, and Mexico and Central America became free of Spanish rule in 1821. Except for the Guianas, the countries of South America became independent of Spain and Portugal between 1810 and 1825. British Guiana did not gain its independence until 1966 (as Guyana), and Dutch Guiana did not do so until 1975 (as Suriname). French Guiana became an overseas département (administrative district) of France.

Canada became a self-governing dominion within the British Empire in 1867 under the terms of the British North America Act. In 1926 Canada, along with the other nations of the imperial Commonwealth, was recognized as an autonomous community within the empire. Not until 1982 did Canada promulgate its own constitution, thus freeing it to implement its own laws without the supervision of the British Parliament. Canada remained a member of the Commonwealth.

Colonization generally persisted for longer in the West Indies than in the rest of the Western Hemisphere. Haiti, which won independence from French rule in 1804, is a notable exception. Cuba and Puerto Rico did not become free of Spain until 1898, when they were ceded to the United States. Cuba soon achieved formal independence. The rest of the West Indies remained under colonial rule until after World War II, when there was a general movement throughout the world to decolonize overseas possessions. Most of the European colonial powers lost their remaining holdings after 1945. Most of the British West Indies, including Jamaica and Barbados, became fully independent. In other West Indian societies, the former colonies were incorporated into their mother country or remained in association with it. Martinique, Réunion, and Guadeloupe became départements of France. The former Caribbean colonies of the Netherlands achieved various degrees of independence within the Dutch kingdom. Puerto Rico became a self-governing commonwealth in association with the United States. 1

Impact

An estimated fifteen thousand spectators watching the lynching of Henry Smith, Feb 3, 1893. 2

Though colonization finally ended in many colonies, we can clearly see the trail it left behind, a trail of inequalities, discrimination, and racism.

The tortuous route where African captives marched to the coast of Ghana, Togo, Angola (not exclusively) often shackled to one another bears witness to this truth. This is the route where amidst raging storms and against a far-reaching network of violence and hatred, naked, chained men, women, and children were reduced to Black cargo in the dreaded slave ship dungeons of the Middle Passage - in which millions of souls still rest at the bottom of the Atlantic.

The route led to the auction blocks in America, the rapes, the slave patrols, the backbreaking life-ending labor at gunpoint, the separation of families and the whipping and lynching which were treated like major events with crowds including children in their Sunday best.

Unfortunately, we cannot bring children to the public square and have them watch someone burned to death, tortured, have their fingers cut off, castrated, taunted, menaced, hanged, and not expect it to have some consequence. The legacy it created is not solely the indifference to how we treat people who look different than us, it is an intergeneration of hate, one that has become a natural phenomenon with no pang of remorse or expression of emotion in evil. This explains why many racists are typically proud of their hate; their environment a powerful antibody to shame; and their behavior symptoms of a systemic ideological cancer that is highly resistant to public humiliation.

As the leading cause of death in many cities, racism is an indicator of both a crisis and a serious challenge that might not be met until this generation of Whites and Blacks pull together and chose hope over fear.

Mindful of the sacrifices borne by our veterans of creative suffering, the men, women, and slave children who endured the lash of the whip, plowed the hard earth till their hands were raw to build the new towns and cities that would eventually become the United States – we can no longer afford indifference to the suffering of colonization.

Chief Yellow Hair and his council stand in front of replicas of teepees at a human zoo at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair. (Library of Congress)

Reference:

- Elihu Burritt and Jemmy Stubbins (2022) “Colonization of the Americas” Encyclopædia Britannica

- Robert McNamara (2019) “1893 Lynching of Henry Smith” Thought Co; also see The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.) 1887-1931, February 02, 1893; Fort Worth Gazette. (Fort Worth, Tex.) 1891-1898, February 02, 1893; Burned at the Stake: A Black Man Pays for a Town's Outrage; and Library of Congress/ Public domain image.