This case study is to enable us to understand that the elimination of genuine pro-independence leaders by colonial masters in places like Africa crippled the continent, with the effects still visible.

In the late 15th Century, an empire known as the Kingdom of Kongo dominated the western portion of the Congo, and bits of other modern states such as Angola. It was sophisticated, had its own aristocracy and an impressive civil service.

When Portuguese traders arrived from Europe in the 1480s, they realized they had stumbled upon a land of vast natural wealth, rich in resources - particularly human flesh.

The Congo was home to a seemingly inexhaustible supply of strong, disease-resistant slaves. The Portuguese quickly found this supply would be easier to tap if the interior of the continent was in a state of anarchy.

They did their utmost to destroy any indigenous political force capable of curtailing their slaving or trading interests. Money and modern weapons were sent to rebels, Kongolese armies were defeated, kings were murdered, elites slaughtered, and secession was encouraged.

By the 1600s, the once-mighty kingdom had disintegrated into a leaderless, anarchy of mini-states locked in endemic civil war. Slaves, victims of this fighting, flowed to the coast and were carried to the Americas.

About four million people were forcibly embarked at the mouth of the Congo River. English ships were at the heart of the trade. British cities and merchants grew rich on the back of Congolese resources they would never see. 1

This first engagement with Europeans set the tone for the rest of the Congo's history. For centuries, colonial powers have played key roles in shaping Congo's destiny. In the period from 1885 to 1908, one of history’s most brutal White Supremacy rulers, the 19th century Belgian King Leopold II, who has been described as worse than Adolf Hitler for his genocidal crimes, successfully transformed the entire Kongo (Congo), a landmass the size of Western Europe, half the area of the United States, 76 times larger than Belgium, and holds vast potential wealth. 2

In April 1884, seven months before the Berlin Congress, the US became the first country in the world to recognise the claims of King Leopold II of the Belgians to the territories of the Congo Basin. 3

The area was handed over to him by 14 European nations and the United States at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 where Africa was shared among European colonists.

Before acquiring the Congo, Leopold failed in purchasing other areas in Asia and Africa including the Philippines from Spain after he was lent money by the Belgian government for his expansion project.

He strategically established the front organization, International African Association, to “civilise the savage people” in 1876. The greedy King hired British journalist and explorer, Henry Morton Stanley, to explore and establish a colony in the Congo region. They used alcohol, trade, and deception to create a relationship with the leaders of the natives and persuaded them to sign treaties ceding their lands to King Leopold. 4

Stanley, Henry Morton in tropical uniform, photo, circa 1880 (pdi)

The kindness turned into savagery as violent force and intimidation was used to enrich the King who exploited the people for decades. He collected and sold ivory before using forced labour to harvest and process rubber in the 1890s when prices soared. Thousands were also sold into slavery, confirmed eyewitness testimonies during an inspection by an international Commission of Inquiry in 1904 led by consul Roger Casement who was appointed by the British Crown.

Leopold II’s claim to the Congo as his personal property including their lands and minerals was recognized after dubiously expressing his initial goal of using his so-called private charitable organisation, the International African Association, to offer humanitarian assistance and civilisation to the natives.

It was rather a horror for the people who were tortured, raped, and killed by the Force Publique - Leopold’s private colonial militia of about 90,000 men, which he used to run the Congo, forcing indigenes to diligently work as slaves.

Local recruits of the Force Publique with a Belgian officer. 5

The Free State with finances that were frequently precarious was intended, above all, to be profitable for Leopold and its white supremacy investors. Early reliance on ivory exports did not make as much money as hoped and the colonial administration was frequently in debt, nearly defaulting on several occasions. However, a boom in demand for natural rubber in the 1890s, however, ended these problems as the colonial state was able to force Congolese males to work as forced labour collecting wild rubber which could then be exported to Europe and North America. 6

The world's largest supply of rubber was found at a time when bicycle and automobile tyres, and electrical insulation, had made it a vital commodity in the West. The late Victorian bicycle craze was enabled by Congolese rubber collected by slave labourers. The rubber boom transformed what had been an unexceptional colonial system before 1890 and led to significant profits. Exports rose from 580 to 3,740 tons between 1895 and 1900. 7

To facilitate further economic extraction from the colony, all vacant land, including forests and were decreed to be "uninhabited" and thus in the possession of the state, leaving many of the Congo's resources (especially rubber and ivory) under direct colonial ownership. 8

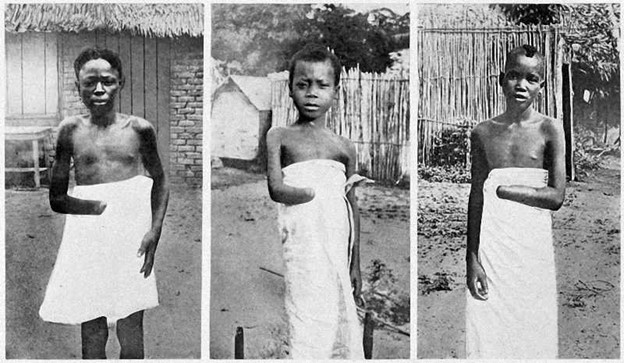

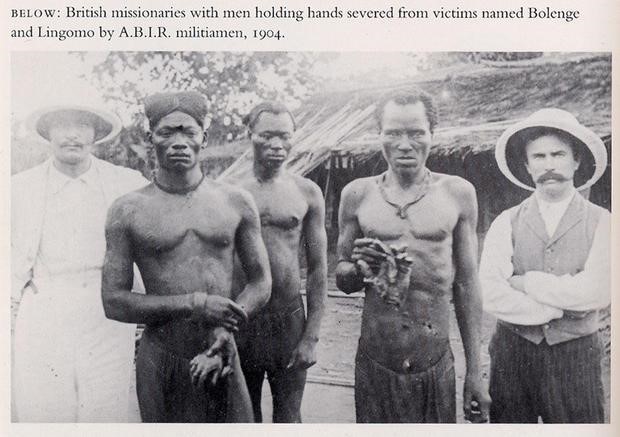

Congolese men were rounded up by the brutal Belgian-officered security force and their wives were interned to ensure compliance and were brutalized during their captivity. The men were then forced to go into the jungle and harvest the rubber. Disobedience or resistance was met by immediate punishment - flogging, severing of hands, and death. 9

With the help of private companies like Antwerp base Société Anversoise, Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company, which was founded with British and Belgian capital, Compagnie du Katanga and Compagnie des Grands Lacs which were all commanded by a European agent and manned with armed sentries to enforce taxation and punish any rebellion, the system became even extremely profitable, making a turnover of over 100 per cent on its initial stake in a single year. 10

Under Leopold II’s watch, loot flowed endlessly from the dark interior of the jungle, up the river Congo and into colonial Belgium. In fact, the King made 70 million Belgian francs' profit from the system between 1896 and 1905, prompting his diabolical system to be copied by other colonial regimes, notably those in the neighboring French Congo. 11

Tribal leaders capable of resisting were murdered, indigenous society decimated, proper education denied, and a culture of rapacious, barbaric rule by a Belgian elite who had absolutely no interest in developing the country or population was created. 12

An undetermined number of Congolese, ranging in the millions, were killed with many well-documented atrocities under the absolute rule of King Leopold II. Estimates of deaths in that period range from 10 million to 15 million Africans, and the debate whether it constituted a genocide continues. 13

Together with epidemic disease, famine, and a falling birth rate caused by these disruptions, the atrocities which contributed to a sharp decline in the Congolese population were particularly associated with the labour policies used to collect natural rubber for export.

Hands of those who couldn’t meet their rubber quotas were severed including those of children, reports a German newspaper in 1896 which stated that 1,308 hands were gathered in one day. 14

Victims of Leopold’s atrocities

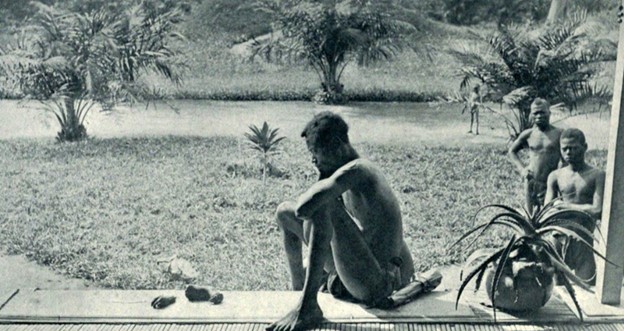

A man sits on a low platform looking at a dismembered small foot and small hand of his five-year-old daughter, who was later killed when her village did not produce sufficient rubber for the brutal, exploitative regime that relied on forced labour to cultivate and trade rubber, ivory, and minerals. 15

Leopold II poured the blood money into Belgium, building huge private and public construction projects across Belgium, the beautiful capital of Europe. The Justice Palace in Brussels is one of the many former symbols of Congolese-derived wealth. 16

The Justice Palace in Brussels, a former symbol of Congolese-derived wealth, undergoing renovation (public domain image)

In the grounds of the King’s palace at Tervuren, he built the Royal Museum of Central Africa to display his spoils, including a "human zoo" in the grounds - featuring 267 Congolese people as exhibits. 17

Royal Museum for Central Africa built with blood money (public domain image)

Despite the large collection of countless colonial objects, buildings that were built with blood money makes no mention of the atrocities committed in the Congo Free State. 18

Congolese people forced to be human exhibits in a "zoo" in Belgium in 1897 (PDI)

When the atrocities related to brutal economic exploitation in Leopold's Congo Free State resulted in millions of fatalities, the US joined other world powers to force Belgium to take over the country as a regular colony. 19

In a move supposed to end the brutality, Belgium eventually annexed the Congo outright in 1908, but the problems in its former colony remained. Mining boomed, workers suffered in appalling conditions, producing the materials that fired industrial production in Europe and America. 20

In World War I men on the Western Front and elsewhere did the dying, but it was Congo's minerals that did the killing. The brass casings of allied shells fired at Passchendaele and the Somme were 75% Congolese copper.

In World War II, the uranium for the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki came from a mine in south-east Congo. Western freedoms were defended with Congo's resources while black Congolese were denied the right to vote, or form unions and political associations. They were denied anything beyond the most basic of educations.

They were kept at an infantile level of development that suited the colonial masters and mine owners but made sure that when independence came there was no home-grown elite who could run the country.

It was not until 1960 that the Republic of Congo was established, after a fight for independence, an envisaged independence that was predictably disastrous. 21

After over a hundred years of colonial enslavement, looting and illegal exploitation of natural resources, Patrice Lumumba, a Congolese nationalist, and firebrand pro-independence leader was determined to achieve genuine independence and to have full control over Congo's resources to improve the living conditions of the people. Unfortunately, Lumumba’s actions were perceived as a threat to Belgium and other colonial interests.

The first Cold War crisis in Africa occurred when Patrice Lumumba, the newly democratically elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), ordered Belgium to pull out of Congo.

At stake was a country that covers half the area of the United States, shares borders with nine other African nations and holds vast potential wealth. Its mineral resources include 65 percent of the world's known reserves of cobalt and large deposits of copper, tin, uranium, gold, oil, and diamonds.

For Belgium the ex-colonial power and its Western allies they were determined to at least hold on to the southern Congolese province of Katanga, rich in copper, uranium, and tin.

And so, Belgium with assistance from Cold War Western alliance helped Moise Tshombe a fellow Congolese to declare secession of the iron-rich Katanga province. This was followed by a staged massacre that falsely implicated Lumumba and no sooner had Belgian troops returned to restore order. 22

Chaos threatened to engulf the region as Cold War superpowers moved to prevent the other gaining the upper hand. 23

Sucked into these rivalries, the struggling Congolese leader requested United Nations peacekeeping forces to protect the country’s territorial integrity and his new government. UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld intervened against the Belgians and Katangese. Dag Hammarskjöld organized a UN armed force to subdue Katanga and save the Congo and Africa from Cold War involvement.

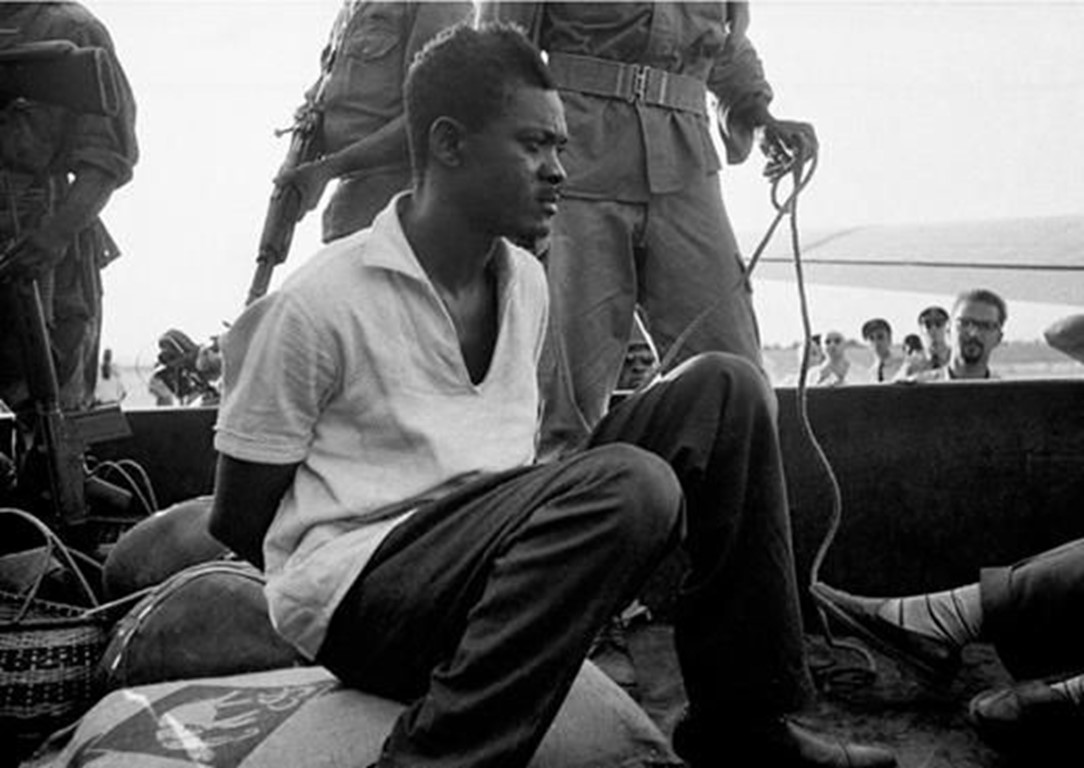

While a desperate Lumumba looked up to Brussel’s rival Moscow for further assistance to safe his country, Brussel with Western backing liaised with Joseph-Desire Mobutu, a onetime Lumumba aide who had a few years before been a sergeant in the colonial police force to take over. Lumumba was horrifically beaten and summarily executed in January 1961 by Western agents, with the complicity of Mobutu and Tshombe. 24

Tied up Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba at the Leopoldville (Kinshasa) airport on December 2, 1960, shortly after his arrest by forces loyal to Colonel Joseph Mobutu (Public Domain Image)

Not long after Lumumba’s brutal murder, Dag Hammarskjold who from the start backed Lumumba was determined to pursue a negotiated solution between Tshombe and the central government, to ensure Congo had a united, strong, stable, legitimate government.

Just after midnight on 18 September 1961, Hammarskjöld was heading to negotiate a ceasefire in a mineral-rich breakaway region of Congo, where another of his peacekeeping missions - United Nations Operation in the Congo forces were getting bogged down by Katangese troops under Moise Tshombe in the complex politics of decolonization and Cold War rivalry.

Mysteriously the UN Secretary-General’s Douglas DC-6 airliner SE-BDY crashed in darkness shortly before landing in a forest near Ndola in Northern Rhodesia - now Zambia and he perished in the crash. 25

Officials search the crash site after the plane carrying Dag Hammarskjold. 26

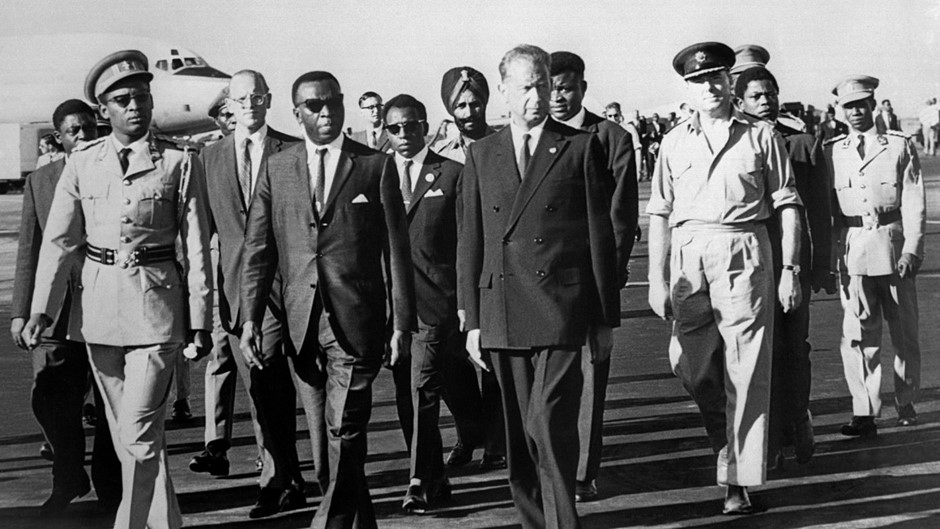

Dag Hammarskjold pictured (2nd from right) on September 13. 1961, just five days before his death, in Leopoldville as part of a peace mission in the region. 27

Though there is overwhelming evidence that foul play was suspected, the world has never been able to piece together the truth despite endless inquiries amid calls for transparency. Much remains hidden in the long-running mystery of Hammarskjöld’s death. 28

The elimination of Lumumba and Hammarskjöld was not through any innate fault of the Congolese, but because it has been in the interests of the all-powerful colonial masters to destroy, suppress and prevent any strong, stable, legitimate government in Congo that can threaten to interfere with the easy extraction of the nation's resources. 29

Following the elimination of the much-loved Lumumba, Congo was subject to enormous centrifugal forces that threatened to tear it apart. With no tradition of statehood or economic reason to look to the central government, its regions tended toward autonomy, its borders, shared with nine other African nations were drawn to settle rivalries between colonial powers without respect for ethnicity, language, culture, natural features, or other factors that go into making a nation.

Years after independence, the country was reeling from almost continuous bloody strife. At stake was abundant mineral deposits including 65 percent of the world's known reserves of cobalt and large deposits of copper, tin, uranium, gold, oil, and diamonds.

With colonial backing Mobutu who had rose to become commander in chief sought to hold the nation together by seizing power by means of a coup in 1965.

Hailed as a bulwark against communism, Mobutu received crucial aid from foreign allies with varying strategic, economic, political, and commercial interests in Africa. His chief patron for much of that time was the United States, which provided about $2 billion in foreign assistance. In return, Washington got a secure base for operations in neighboring Angola, where Western-backed UNITA rebels were locked in a long civil war with a Marxist government supported by Cuban troops and Soviet arms.

At crucial points, his key allies in Europe - Belgium and France sent paratroopers to help him quell disturbances. But it came at a price. While Belgium was free to do as it pleases, France was granted a base in h country for operations in Chad and elsewhere in its former African empire. 30

And so, Mobutu became a tyrant. In 1972 he changed his name to Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga, meaning "the all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake".

Dissidents were tortured or bought off, ministers stole entire budgets, government atrophied. The West allowed his regime to borrow billions, which was then stolen, and today's Congo is still expected to pay the bill.

The West tolerated him as-long-as the minerals flowed, and the Congo was kept out of the Soviet orbit.

He, his family, and friends bled the country of billions of dollars, a $100m palace was built in the most remote jungle at Gbadolite, an ultra-long airstrip next to it was designed to take Concorde, which was duly chartered for shopping trips to Paris. 31

In 1997 an alliance of neighboring African states, led by Rwanda - which was furious Mobutu's Congo was sheltering many of those responsible for the 1994 genocide - invaded, after deciding to get rid of Mobutu.

A Congolese exile, Laurent Kabila, was dredged up in East Africa to act as a figurehead. Mobutu's cash-starved army imploded, its leaders, incompetent cronies of the president, abandoning their men in a mad dash to escape.

Mobutu took off one last time from his jungle Versailles, his aircraft packed with valuables, his own unpaid soldiers firing at the plane as it lumbered into the air.

Once installed however, Kabila, Rwanda's puppet, refused to do as he was told. He was assassinated and was succeeded ten days later by his 29-year-old son Joseph Kabila in the context of the Second Congo War. 32

During Joseph Kabila’s reign between January 2001 and January 2019, foreign armies clashed deep inside the Congo as the paper-thin state collapsed totally and anarchy spread. Hundreds of armed groups carried out atrocities, millions died.

Ethnic and linguistic differences fanned the ferocity of the violence, while control of Congo's stunning natural wealth added a terrible urgency to the fighting. Forcibly conscripted child soldiers corralled armies of slaves to dig for minerals such as coltan, a key component in mobile phones, the latest obsession in the developed world, while annihilating enemy communities, raping women, and driving survivors into the jungle to die of starvation and disease.

Despite a deeply flawed, partial peace which was patched together, in the far east of the country, there is once again a shooting war as a complex web of domestic and international rivalries see rebel groups clash with the army and the UN, while tiny community militias add to the general instability.

Although Joseph Kabila was succeeded by Félix Tshisekedi in the country's first peaceful transition of power since independence, the situation of most Congolese has hardly improved under Mr. Tshisekedi, whose powerful predecessor, Joseph Kabila, still looms in the background.

With a country of countless shanty towns of displaced, poverty-stricken Congolese, roads that no longer link the main cities, and healthcare that depends on aid and charity, the new regime is as grasping as its predecessors. 33

A place seemingly blessed with every type of mineral, the billions of dollars minerals have generated have brought nothing but misery and death to the very people who live on top of them, while enriching a microscopic elite in the Congo and their foreign backers and underpinning technological revolution in the developed world. Consistently it is rated lowest on the UN Human Development Index, where even the more fortunate live in grinding poverty.

The Congo's apocalyptic present – a war torn place filled with rape victims, rebels, bloated politicians, and haunted citizens that has ceased to function - people who struggle to survive in a place cursed by a past that defies description, a history that will not release them from its death-like grip. More than five million people have died, millions more have been driven to the brink by starvation and disease and several million women and girls have been raped - is a direct product of decisions and actions taken over the past five centuries.

Unfortunately, powerful transgenerational colonial masters continue to deliberately stifle the development of a strong state, army, judiciary, and education system, because it interferes with their primary focus, making money from what lies under the Earth. 34

Reference

1. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

2. Ismail Akwei (2019) “How Congo became the private property of Leopold II of Belgium who exploited and butchered millions” Face2Face Africa; also see Benas Gerdziunas (2017) “Belgium's genocidal colonial legacy haunts the country’s future” independent.

3. Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja (2011) Patrice Lumumba: the most important assassination of the 20th century, The Guardian

4. Ismail Akwei (2019) “How Congo became the private property of Leopold II of Belgium who exploited and butchered millions” Face2Face Africa

5. Ismail Akwei (2019) “How Congo became the private property of Leopold II of Belgium who exploited and butchered millions” Face2Face Africa

6. Stengers, Jean (1969). "The Congo Free State and the Belgian Congo before 1914". In Gann, L. H.; Duignan, Peter (eds.). Colonialism in Africa, 1870–1914. Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 261–274; also see Renton, David; Seddon, David; Zeilig, Leo (2007). The Congo: Plunder and Resistance. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-485-4.

7. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC; also see Stengers, Jean (1969) pp. 261–274; Renton, David; Seddon, David; Zeilig, Leo (2007).

8. Van Reybrouck, David (2014). Congo: The Epic History of a People. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-756290-9. p. 79; also see Stengers 1969, p. 265.

9. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

10. Renton, David; Seddon, David; Zeilig, Leo (2007). p. 38.

11. Vangroenweghe, Daniel (2006). "The 'Leopold II' concession system exported to French Congo with as example the Mpoko Company." Revue belge d'Histoire contemporaine-Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis pp. 323–6, also see Slade, Ruth M. (1962). King Leopold's Congo: Aspects of the Development of Race Relations in the Congo Independent State. Institute of Race Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 177.

12. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

13. Benas Gerdziunas (2017) “Belgium's genocidal colonial legacy haunts the country’s future” independent

14. Ismail Akwei (2019) “How Congo became the private property of Leopold II of Belgium who exploited and butchered millions” Face2Face Africa

15. Georgina Rannard & Eve Webster (2020) “Leopold II: Belgium 'wakes up' to its bloody colonial past” BBC News; also see Ismail Akwei (2019) “How Congo became the private property of Leopold II of Belgium who exploited and butchered millions” Face2Face Africa

16. Benas Gerdziunas (2017) “Belgium's genocidal colonial legacy haunts the country’s future” independent; also see Ismail Akwei (2019) “How Congo became the private property of Leopold II of Belgium who exploited and butchered millions” Face2Face Africa

17. Georgina Rannard & Eve Webster (2020) “Leopold II: Belgium 'wakes up' to its bloody colonial past” BBC News; also see Ismail Akwei (2019) “How Congo became the private property of Leopold II of Belgium who exploited and butchered millions” Face2Face Africa

18. Ismail Akwei (2019) “How Congo became the private property of Leopold II of Belgium who exploited and butchered millions” Face2Face Africa

19. Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja (2011) Patrice Lumumba: the most important assassination of the 20th century, The Guardian

20. Georgina Rannard & Eve Webster (2020) “Leopold II: Belgium 'wakes up' to its bloody colonial past” BBC News; also see Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

21. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

22. Walter A. McDougall (2020) “Century International Relations: Tension and Cooperation at the turn of the Century” Encyclopaedia Britannica

23. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

24. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC; also see Walter A. McDougall (2020)

25. Halberstam, David (19 September 1961). "Hammarskjold Dies in African Air Crash; Kennedy Going to U. N. In Succession Crisis". The New York Times. p. 1; also see Hamilton, Thomas J. (23 September 1961). "Interim U.N. Head is Urged by Rusk; His Timing Scored". The New York Times. p. 1; and Stephanie Hegarty (2011) “Dag Hammarskjold: Was his death a crash or a conspiracy?” BBC

26. Officials search the crash site after the plane carrying Swedish diplomat Dag Hammarskjold came down near Ndola in Northern Rhodesia (later Zambia), Central Press/Hulton Archive/Public Domain Images; also see Sarah Pruitt (2019) “UN Leader Dag Hammarskjold Died in Mysterious Circumstances in 1961. What Really Happened? New evidence supports a theory that the pioneering U.N. secretary general was assassinated.” Universal History Archive

27. Dag Hammarskjold pictured on September 13, 1961, just five days before his death, in Leopoldville as part of a peace mission in the region. AFP/Public Domain Images; also see Sarah Pruitt (2019) “UN Leader Dag Hammarskjold Died in Mysterious Circumstances in 1961. What Really Happened? New evidence supports a theory that the pioneering U.N. secretary general was assassinated.” Universal History Archive

28. Sarah Pruitt (2019) “UN Leader Dag Hammarskjold Died in Mysterious Circumstances in 1961. What Really Happened? New evidence supports a theory that the pioneering U.N. secretary general was assassinated.” Universal History Archive

29. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

30. J. Y. Smith (1997) “Congo Ex-Ruler Mobutu Dies in Exile” Washington Post; also see Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

31. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

32. John C. Fredriksen, ed. Biographical Dictionary of Modern World Leaders (2003) pp 239–240.; also see Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

33. Félix Tshisekedi has accomplished little in Congo: The Economist 08/02/2020; also see Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC

34. Dan Snow (2013) “DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth” BBC